Church History

The Site

The Country in the City

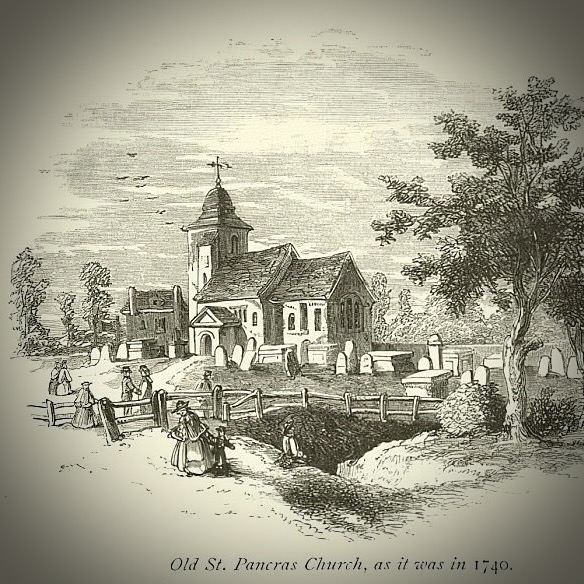

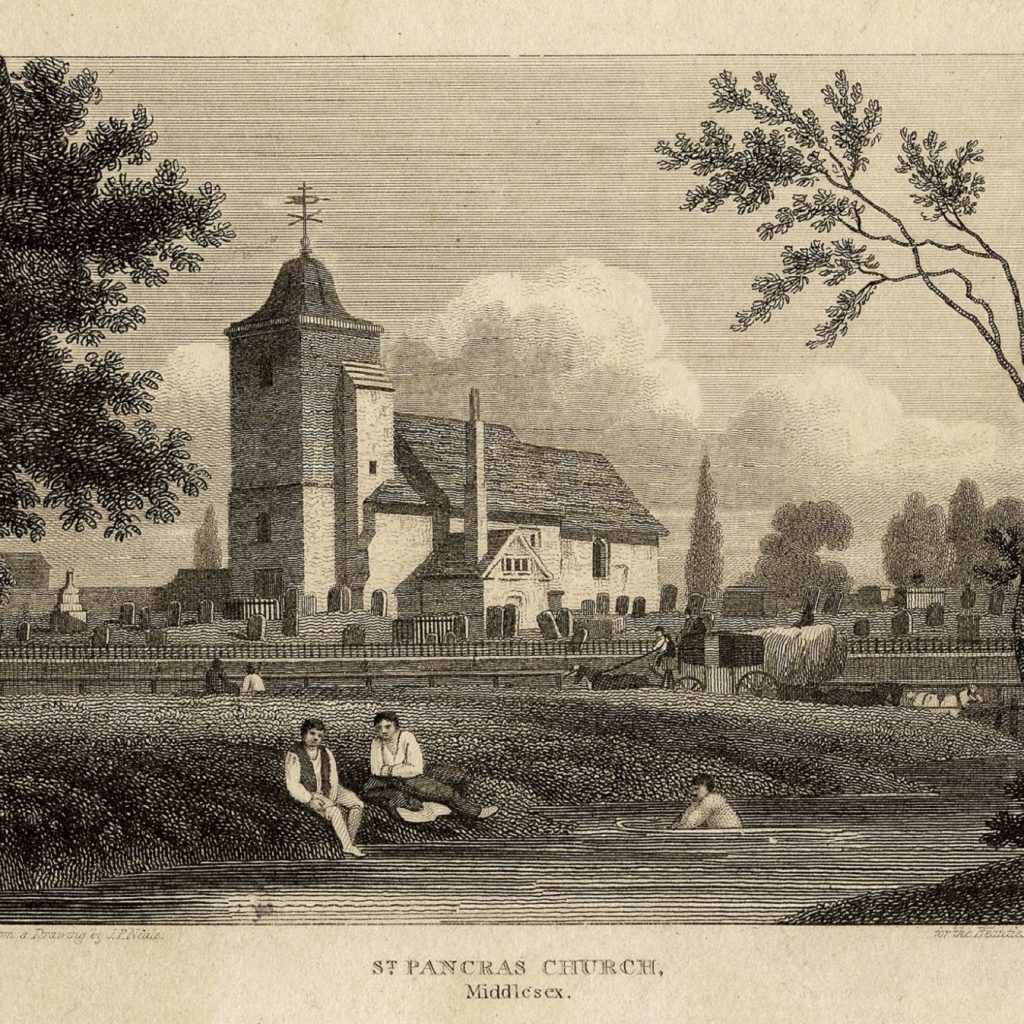

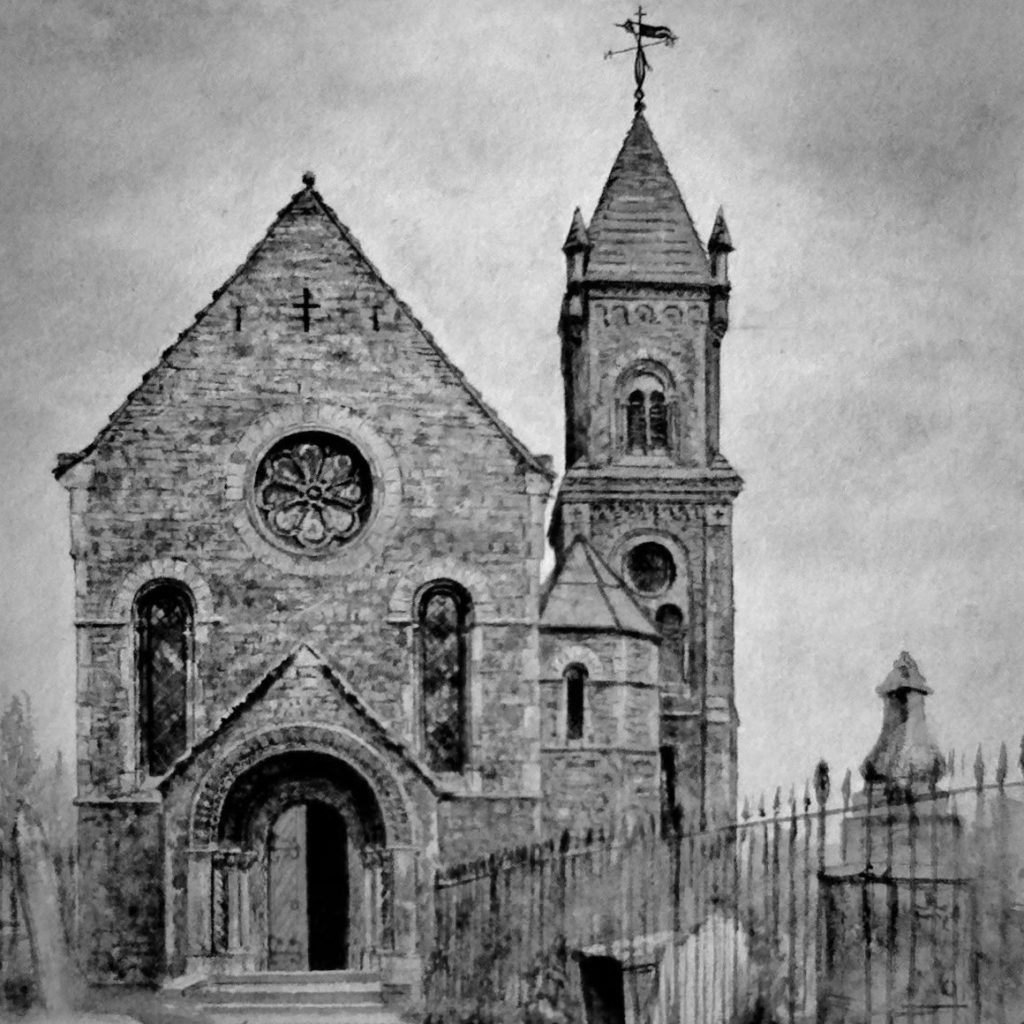

St Pancras Old Church has the appearance and atmosphere of a much-loved country church in the heart of London, which is, after all, exactly what it is. Here it stands as witness to the enduring faith for which its young patron, Saint Pancras, died in 304. “It has lived through wars and rebellions, tumults and storms; suffered neglect and been deserted; received lavish and devoted care,” and it remains the house of prayer and heart of the community it was always meant to be.

The Shrine on a Hill

In the past, the little hillock on which the church now stands rose above the flood valley of the River Fleet. Historians have suggested that a Roman encampment was based here, sloping down towards Kings Cross and Euston. The hill may have been the site of a rural shrine, which was later converted to Christian use, making St Pancras Old Church one of the oldest sites of Christian worship in London. Recycled Roman tile can still be found in our exposed medieval wall. Whether this is a legacy of the Roman camp, or a testimony to the resourcefulness of medieval builders is impossible to tell.

The First Church

The suggestion that St Pancras Old Church dates back to Roman times has a long tradition, with most suggesting that it was founded in 313 or 314. Most churches in England named for the martyr St Pancras have, or may have, ancient origins, suggesting that veneration of the saint spread quickly after his death in 304. While we cannot say for certain that St Pancras Old Church sat atop this hill over the Fleet in 314, the legend of its ancient founding has fascinated visitors tor centuries. As an anonymous poet wrote in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1749:

To Rev'rend spire of ancient Pancras view,

To ancient Pancras pay the Rev'rence due.

Christ's sacred Altar there first Britain saw

And gaz'd and worshipp'd with an holy awe.

Whilst pitying Heav'n diffus'd a saving ray

And heathen darkness chang'd to Christian day.

In the Demesne of St Paul’s

By the eleventh century, records of St Pancras, in the demesne (or domain) of St Paul’s, appear. The Domesday Book of 1085, conducted after the Norman invasion, records “At S. Pancras, Walter, a Canon of S. Paul’s holds one hide. There is a plough there, and twenty-four men who render thirty shillings yearly. The land lay and lies in the demesne of S. Paul’s.” St Pancras Old Church retains a relationship with St Paul’s to this day: the Dean and Chapter of the Cathedral are our Patrons and as such have responsibility of presenting a new Priest to the Bishop when a vacancy arises.

By the twelfth century we find records of the St Pancras Old Church and its vicars. The first recorded vicar was Fulcherius, who was made vicar in 1181 with the annual pension of 2 shillings. In the thirteenth century there was a survey done of the church, recording the mass book, with musical notes and calendar, manuals, psalters, vestments, candlesticks, and “a white silver chalice”. There were 36 houses in the area, as well as a number of manor houses, including that of Adam de Basing, who became Mayor of London in 1252.

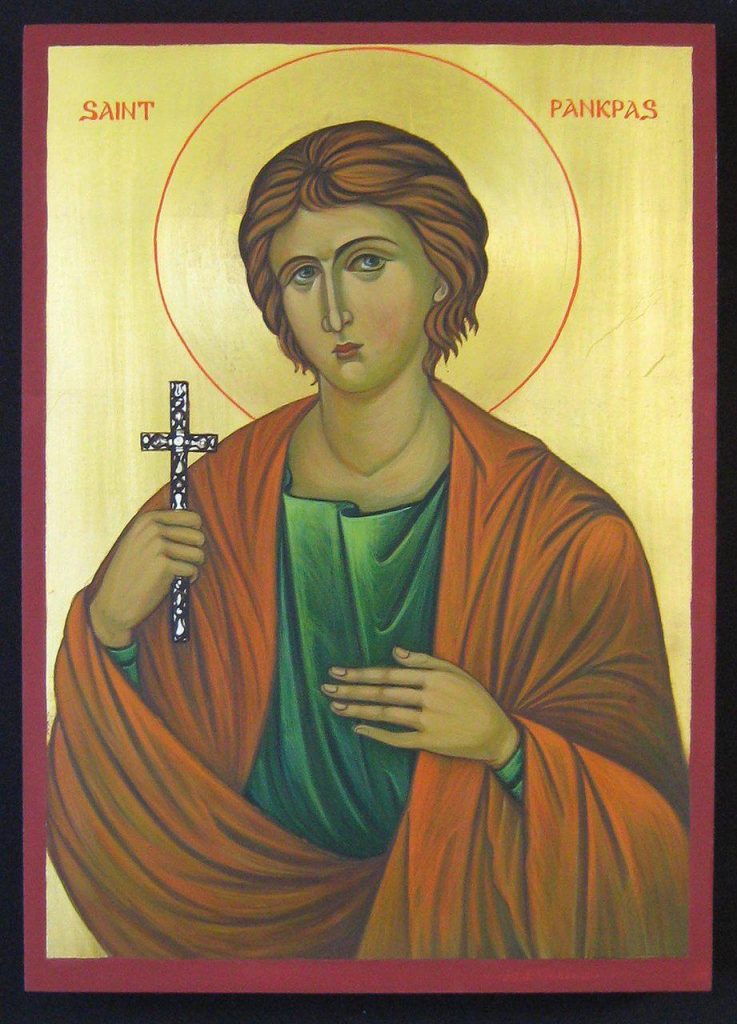

The Saint

A Young Martyr

St Pancras was beheaded by order of the Emperor Diocletian in the year 304. He was about fourteen years old, which is why he is now a patron saint of children. Raised by his uncle after his parents’ death, he converted to Christianity as a boy. Called before Diocletian and commanded to worship Roman gods, Pancras refused and was sentenced to death. The emperor was inclined towards mercy due to his young age, but Pancras refused the offer of clemency and was executed along with the rest of his Christian community. In the sixth century the Basilica of St Pancratius was built over the site of St Pancras’s martyrdom. St Augustine, the first archbishop of Canterbury, was sent by Pope Gregory to England in 595 with relics of St Pancras. He established churches in Canterbury and London.

The Church Building

The Mists of Time

Although many restorations have obscured the view of the distant past of our church, clues remain in our exposed medieval wall and Roman tile eleventh-century altar stone and thirteenth-century piscina. From the thirteenth century, the church fell increasingly into disrepair. A survey in 1 297 noted that “the churchyard is befouled by animals” and that the roof was in desperate need of repair. The church seems to have escaped the ferocity of the Reformation; legend holds that St Pancras Church was a favourite of Elizabeth I, who allowed Latin mass to continue there, and the memorial to her cook can still be seen on the south wall. St Pancras Old Church didn’t, however, escape action during the English Civil War. In November 1642, the Parliament ordered the “deserted Church of St Pancras to be disposed unto lodging for fifty Troupers”. It was probably at this time that the remaining treasures at St Pancras were hidden under the tower.

At this time St Pancras was part of a very small rural community, still well outside the boundaries of London. In 1593, John Norden, the topographer, gave a vivid description of the isolation of the parish church: “Pancras Church standeth all alone, as utterly forsaken, old and weather-beaten … About this church have bin many buildings now decayed, leaving poor Pancras without companie or comfort”. The survey of 1650 describes it standing ” …in the fields remote from any houses in the said parish.” More than once the vicar and parishioners had to abandon worship in the church to escape the “foul’d ways and great waters” of the Fleet. Its primary use was as a burial ground, as well as a place to go for a quick wedding, with no questions asked. It was probably for this reason that Mary Wollstonecraft, pregnant with her daughter, and William Godwin were married here in 1797. She was buried in the churchyard later that year

The Turn of the Tide

In 1822 St Pancras New Church was opened, and St Pancras Old Church fell into disuse. By the 1840s it was virtually in ruins. The industrial expansion of London, however, meant that St Pancras now sat in a fully populated area, and in 1847-1848 the church underwent a complete restoration.

Churchyard

The churchyard accommodated almost 100,000 burials in the 150 years before it was closed in 1854, including those of Johann Christian Bach, Chevalier D’Eon, John Flaxman, William Franklin, William Godwin, John Polidori and Sir John Soane, whose Grade I listed tomb still stands here. A local resident wrote to The Times in 1850 complaining that “More than 25 corpses . .. have been deposited every week for the last 20 years in an already overcrowded space; and at this very time they are burying in it at nearly twice that rate . . teeth, bones; fragments of coffin wood are seen lying in large quantities around these pits”. Charles Dickens often visited the churchyard, and it features in his Tale of Two Cities as the site of “fishing”, or body snatching.

In the 1860s, over 10,000 graves were excavated to make way for the new London train terminus at St Pancras Rail Station. The poet Thomas Hardy was employed in this task, giving rise to one of the churchyard’s most iconic sights, the “Hardy Tree”. In 1877 the churchyard was transformed into an expansive Victorian garden and the church underwent further refurbishment in 1888. More detail on the churchyard can be found on the Churchyard History page.

A Rediscovery

The architect, A. D. Gough, sought to renovate the church in line with its twelfth-century foundations, adding new windows and doors, a new north vestry and removing the west tower, adding one on the south wall instead. While excavating in the old foundations of the west tower, the workmen stumbled across a trove of treasures, which had probably been hidden there during the course of the English Civil War when the church had been used as military lodgings. Six feet down under the floor of the tower they found an exquisite Elizabethan silver chalice, an Elizabethan/ Jacobean flagon and an Elizabethan paten that is used every Sunday at mass. They also uncovered an altar stone, believed to be from the eleventh century, which was restored to its place in the centre of the High Altar, and still used in the celebration of mass today. It is believed to be the most ancient artefact in Camden.

The Future of St Pancras Old Church

The community around St Pancras Old Church has grown like never before in the past decade. In 2002-2003, to make way for the new High Speed 1, St Pancras’s churchyard was thoroughly excavated, and a report published on the thousands of graves they found there. The arrival of more train links has meant more visitors to the area, and St Pancras Old Church has become a welcome home-away-from-home for visitors to London. In addition, the King’s Cross area has recently seen an unprecedented development, welcoming in thousands of new residents and visitors, who now have the opportunity to share in the history of this building.

St Pancras Old Church has worked to open its doors to this growing community. The Church is open every day of the year, and St Pancras Old Church has become a noted concert venue in North London. Various small restoration projects, on the clock, organ and floor, have taken place, and disabled access work was completed in order to keep the Church open to all, click here to read more about our current restoration plans. A part of the community for over a millennium, through wind, war and change, St Pancras Old Church still stands on its hillock, welcoming all to share in its history and worship.